What is the Competitive Balance Tax?

Let’s start with what the competitive balance tax (CBT) does financially. In the 2023 season, the threshold was $233 million. Any payroll figures that finish below that figure are safe from these surcharges. The Los Angeles Angels had a CBT payroll number of $232,971,346, so they avoided a tax bill by just $28,654, less than the cost of a used Ford F-150. The Pittsburgh Pirates also avoided a tax bill, safely in the tax-free zone with $143,225,066 to spare.

What about the 8 teams that exceeded the CBT? Well, that depends. The system is designed to ding repeat offenders at increasingly higher rates, presumably in hopes of getting those teams to get back in compliance. It’s like when an owner tries to teach a cat not to jump on the kitchen counter. First, she’ll try a stern warning. Next, she’ll get a spray bottle filled with water. Then maybe a sticky paper trap. And finally, exasperated, she’ll just put up an electric fence. Most cats, however, employ the New York Mets approach and laugh at these attempts, living comfortably atop their perch on the counter.

A team over the threshold under the current agreement will pay a 20% tax bill on every payroll dollar over that year’s figure. That math is easy:

Team X Payroll: $243,000,000

CBT Threshold: $233,000,000

Amount subject to tax: $10,000,000

1st time offender, 20%: $2,000,000 bill

That $2 million is on top of the existing $10 million. Meaning, if a team is at the threshold and signs a player for $10mil, they will have to pay that player his salary as well as pay an extra $2 million tax, effectively making that signing $12 million on the balance sheet.

A team that exceeds the threshold in consecutive seasons gets bumped up to a 30% tax rate. And any team going over for 3 consecutive years or longer is hit at 50%. The same $10 million signing would effectively cost a habitual offending team $15 million.

Many big-spending teams are okay with paying the 20%, but by year 3 or longer, may start to balk at the 50% rate and work to get their payroll back under the threshold. Any full season under the threshold resets a team’s consecutive overage streak back to zero, meaning their next season over the limit will be back at the 20% rate, not whatever they paid previously.

Newly added to this current collective bargaining agreement are escalating penalties for how far over the threshold a team goes. A team that goes between $20 to $40 million over the threshold pay 12% for the dollars in that range. Going from $40 to $60 million is 42.5% (and 45% for consecutive seasons), and a team going more than $60 million over the threshold will pay a 60% surcharge on every dollar. In 2023 that super threshold was $293 million.

So the real world examples of this can range from simple to as complex as the US tax code.

A simple case is the Texas Rangers, who went $9,135,712 over the threshold in 2023. As first-time offenders, the have an easy equation:

Overage: $9,135,712

Tax Rate: 20%

Tax Bill: $1,827,142

Now for the advanced course: the New York Mets had a luxury tax payroll of $374,676,003, putting them $141,676,003 over the threshold. (By the way, $141 million would have ranked as the 22nd highest payroll alone). The Mets just completed a second consecutive season over the threshold, meaning their rate starts at 30%. But they also went into the super threshold last year, as they had for 2022. So, they have the following math performed:

Overage: $141,676,003

2nd Year Tax Rate: 30%

Tax Bill: $42,502,800

PLUS Surcharge Level 1: ($20,000,000 x 12%) = $2,400,000

PLUS Surcharge Level 2: ($20,000,000 x 45%) = $9,000,000

PLUS Surcharge Level 3: ($81,676,003 x 60%) = $ 49,005,601

2023 TOTAL TAX BILL: $102,908,403

Steven Cohen net worth: $19,800,000,000

That tax bill works out to only 0.52% of his net worth.

Where does the money go? In 2023, $210,252,163 is due to be paid by 8 clubs this season. The first $3.5 million of taxes go toward player benefits. Then the remainder is split 50/50 between player retirement accounts and into the revenue sharing pool. Meaning nearly $100 million is due to be allocated to those clubs.

I’m not a lawyer, so this is all way too convoluted for me. It’s like going to the nerd’s house for a game of Monopoly and he’s got the ticker tape calculator out to calculate tax rates, mortgages, and deed auctions. All this to save filthy rich owners from even filthier, richer owners.

Where did the tax come from?

Coming out of the devastating 1994-95 players’ strike, baseball got some new financial rules. From 1997 to 1999, there was a complex calculation to keep rich teams from overspending. First, the 5th and 6th highest payrolls were averaged. For example, if #5 was $100 million and #6 was $98 million, the threshold would then become $99 million. Then, for the top 5 payrolls in the league, every dollar they spent over that calculated threshold was taxed at 34%. Eight teams paid luxury taxes during this span, including, surprisingly, the Marlins. The highest bill was the 1999 Yankees for $4.8mil.

From 2000 to 2002, there was no competitive balance tax (the last days of the Wild West). It was brought back in 2003 where the threshold was introduced. Though the percentages and surcharge thresholds have changed yearly, the idea is the same as it is today (the 2003-2021 seasons did not include the super taxes, or the Steve Cohen rule, that was implemented effective 2022).

Though the Players Union will never agree to a salary cap, they agreed to this as it was either that or the cap. And the rich teams will spend anyway (just look at the amount of money thrown at players these days), plus the players get benefits accrued into insurance and retirement plans.

But has the luxury tax been good for baseball?

There are signs emerging that this system isn’t working as intended. Instead of a “soft cap”, a de facto salary cap that uses the tax bills to deter overspending, teams are increasingly speeding through the yellow light, opting to pay the fine later. In 2019, three teams, the Red Sox, Cubs and Yankees all exceeded that year’s $206 million threshold and collectively paid $14 million in taxes. In 2023, eight teams surpassed the threshold and owe $210,252,163 to the tax man (i.e. the Commissioner’s Office).

What changed in those 4 years?

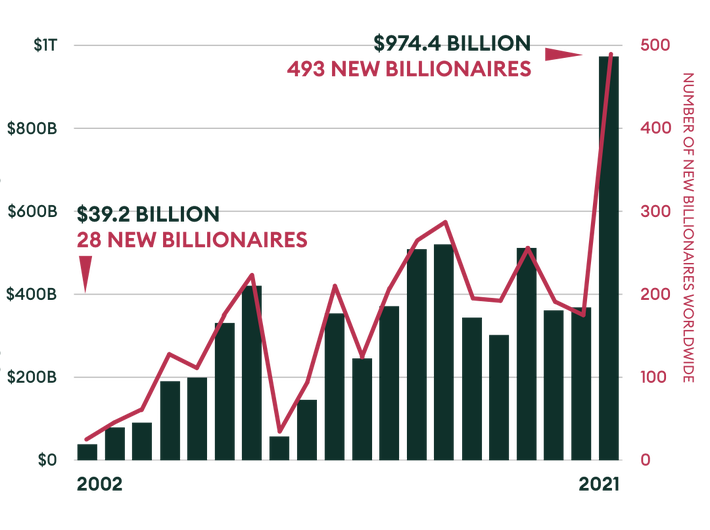

The 1% (where you’ll find team owners) has increased their concentration of wealth immensely in that time frame. When billionaire wealth has grown 33% in the past 4 years, the intended effect of the competitive balance tax is muted. A $100 million tax bill is 10% of a billionaire’s net worth, yet only 0.52% of Steve Cohen’s. So again, we have the same scenario of “small market” teams trying to keep up with the big markets and big pockets. Except this time, everyone is already ultra rich and the revenue flowing throughout Major League Baseball is massive and obscene.

I think this shows that we’re back where we were in 1995. Sure, teams would rather not pay any tax. But if that’s the price of winning, that’s what they’ll do. Five of the 12 playoff teams came from this group of 8, including 2 of the 3 100-win teams and the World Series champions. The Padres were generally seen as unlucky, with their expected win total 9 wins higher than actual, which would have gotten them a top wild card spot. The Yankees and Mets, while having disappointing seasons, still finished near .500, which is the floor one would expect for that much money.

Were this rule working as intended, a $10 million player would not be signable by a team looking to lower their tax number. He would have to play for a club with a lower payroll. In theory, that balances the playing field. For example, last year Brandon Belt signed with the Blue Jays (a luxury tax team) for 1 year and $9.3 million. While he only played 104 games, and just 29 in the field because Vladimir Guerrero Jr is their everyday first baseman, his bat was worth 18 runs above average, which would rank 8th among all first basemen in 2023, including 4 runs more than Vladdy Jr.

I’m not saying Brandon Belt is the missing roster piece for a championship team (although he does have some rings). But a productive veteran first baseman for $9.3 million would have been an improvement for many teams. Imagine his 2.3 fWAR for the NL Central-winning Brewers, who used a motley crew of Rowdy Tellez, Carlos Santana, Owen Miller and Luke Voit to put up 23 home runs and a slash line of .231/.292/.389 over 674 plate appearances. Brandon Belt was .254/.369/.490 in 404 plate appearances with 19 home runs.

The Blue Jays were already projected to be over the threshold for 2023 when they signed Belt. They signed him knowing part of his salary would be taxed. His total cost to ownership was $10,920,000. The Brewers had a 2023 payroll of $151 million, over $100 million lower than the Blue Jays. They arguably needed him more, considering each team’s incumbent first base options going into 2023. But because the CBT is no longer a major deterrent, the mid-market Brewers don’t get access to this tier of player if a big budget team wants them instead.

Basically, if you’re a veteran looking at a one-year deal in the $10 to $20 million range, and the luxury tax teams (largely the teams who “win the offseason” and look best on paper) aren’t deterred from offering you market value, why wouldn’t you sign with a team with a better chance to win all other things being equal?

But you also must look at the bottom payroll teams and wonder what is going on there. Many of these teams, such as the Pirates, Royals and A’s, have been receiving revenue sharing money for decades now. It would be hard to argue that they consistently fielded the best team they possibly could with their resources available. Take that $10 million player, the one who costs a luxury tax team at least $2 million, but now place him on the Pirates. Say he gets $12 million to don the black and gold, who given their history must pay a premium. Well, if the Pirates are receiving a significant portion of revenue sharing, does that not subsidize that player’s contract a certain amount?

The major selling point to fans of the other American sports leagues with caps is the concept of parity. Hockey and football have hard caps, the NBA has a cap, but who the hell knows how it works. The NHL basically says, here’s your limit, both the minimum and the maximum. Now slap a team together and let’s see who comes out on top. Since the salary cup came to the NHL, 23 of the now 32 teams have been to a Stanley Cup final, 71% of the league. I think making the championship is a memorable season, win or lose, but merely making the playoffs in today’s sports environment not so much. So I’m going to go with how many markets got represented on the big stage. For the salary-capped NFL in that span, that number is 20 of 32, 63%. The World Series is at 18 different teams. The NBA is too star-dependent to compare, so that leaves MLB with the lowest amount of parity.

Has the competitive balance tax assisted lower revenue teams to compete? Yes to an extent, but not as much as a salary floor and cap would. It gives teams a better chance to make the postseason, but going on a long run requires a different, hardier type of team. Of the past 18 World Series matchups, the top one-third of payrolls have produced two-thirds of the competitors. Only four teams, all runners-up, have made the World Series with a payroll ranked worse than 20th. Even more concentrated, the top 5 payrolls any given season have produced 13 of the 36 teams to make the World Series. That is 16.6% of teams getting 36.1% of the slots.

So then is it working? I don’t think it is. It was sold to the fans as a way to keep smaller markets in play. Now everyone can afford to play in that end of the sandbox with revenues at what they are, even with the pending bust of regional tv deals. I do think player salaries have ballooned into laughably inflated figures. But many teams are also bringing in too much money to know what to do with. If the threshold isn’t working as a deterrent as intended and there’s no requirement on how the bottom-payroll clubs allocate their share, then it’s just wealth redistribution amongst billionaires. The easiest thing would be to require teams receiving money to spend a sizable chunk of that on their payroll, like on top of what other meager salaries they were intending to roster.

But the egalitarian thing to do would be abolish this whole Competitive Balance Tax, i.e. billionaire socialism, and change it up. Make teams spending too much pay a Fan Appreciation Tax. Any amount they go over the threshold gets reallocated amongst all 30 teams. Yes, continue funding player retirement and health benefits with half. But don’t give lousy businessmen like John Fisher and Robert Nutting more handouts. Take the $100 million of this year’s tax bill and subsidize costs for fans. MLB.tv could be lowered to $49.00 a year with no blackouts. Five-dollar parking or a discount for taking public transit. Free tickets for good students. Fund programs to help get low-income individuals and families to the park at a greatly reduced cost for a couple games a season. Grow your fan base, invest in the community. If I can forgo my fantasy football 2023 winnings and instead have it donated to charity, owners can skip out on a 7th summer home and work on some PR.

But that would make too much sense. Let’s just keep throwing out $40 million yearly salaries and funnel hundreds of millions of dollars into this elite group of team owners.