Interview #60: Will Bardenwerper

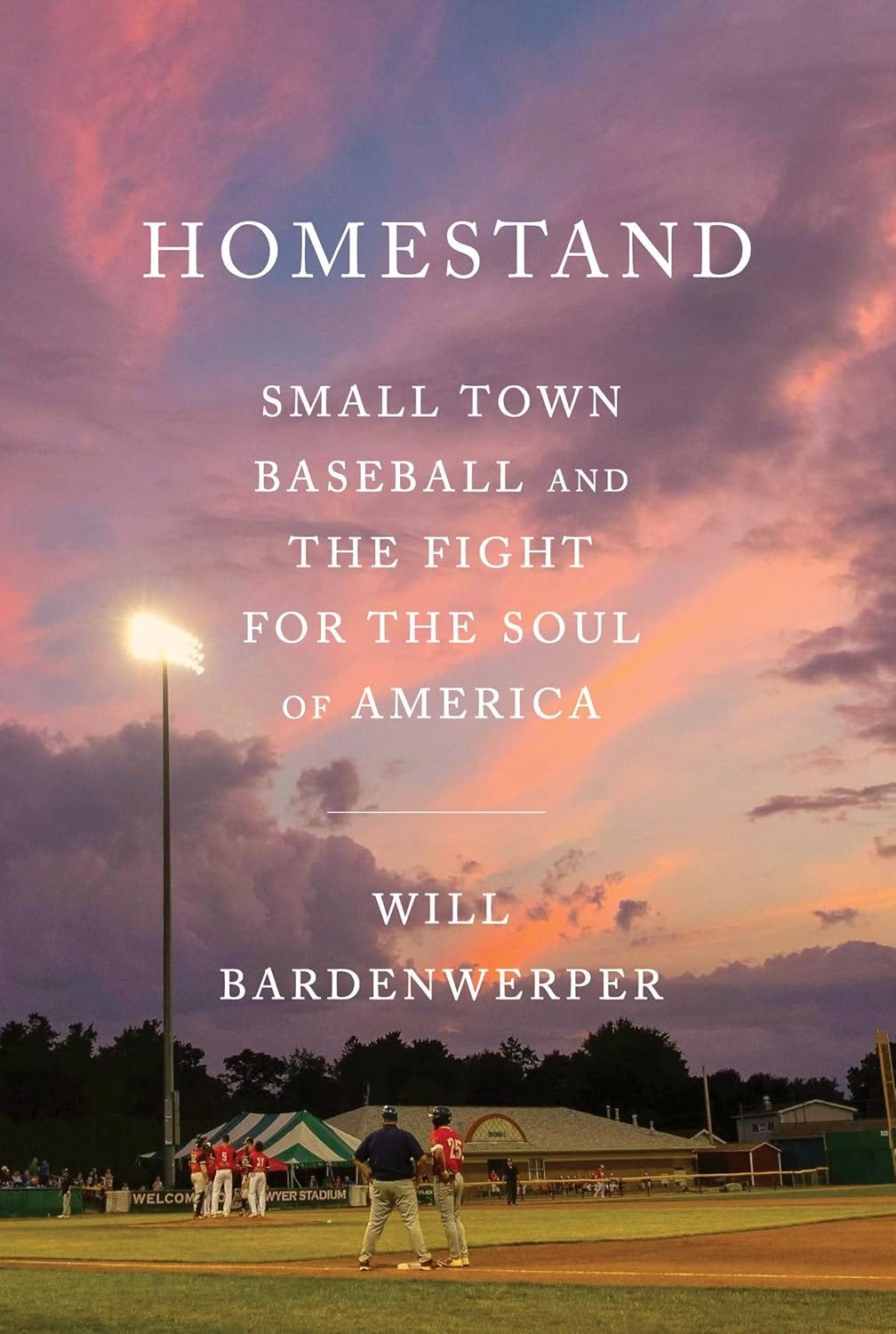

Author of the new book Homestand: Small Town Baseball and the Fight for the Soul of America

Will Bardenwerper is an accomplished writer who has had his work published in many prominent outlets, including The New York Times, Washington Post, Outside, and Newsweek. He published his first book, The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid, in 2017. In March of 2025, Homestand: Small Town Baseball and the Fight for the Soul of America (Amazon link), hit shelves. Before his writing career, he was a Princeton grad who enlisted in the army after 9/11, ultimately spending a 13-month deployment in Iraq in the mid-2000s. From DC in the 1970s after the Senators left for good, he grew up a huge baseball fan and never lost his passion for the sport.

But like many fans born before 2000 (in this case, 1976), he has grown wary of the increasingly tone-deaf way Major League Baseball and the owners of the 30 franchises have acted in pursuit of growing revenue. In the past decade, the ruthless, profit-over-people mindset has blossomed among the front offices and executives. With ever-expanding rosters of data scientists and performance coaches, ownership groups have convinced themselves they’re more efficient than ever at recognizing and developing the elite talent needed to win a World Series. This, along with the cancellation of the 2020 Minor League season, has led to drastic changes to Minor League Baseball (MiLB).

Before the 2021 season, MiLB was restructured to four affiliated farm teams to each of the 30 major league teams, or 120 total. That left 42 teams without a chair when the music stopped. Even the names of the leagues were lost. The Pacific Coast League, which had been part of the baseball landscape since 1903, was now just “Triple-A West”. MLB managed to acquire those naming rights and the league names returned in 2022, but not all the teams.

Will’s book is the perfect way to dive in to the answers to those questions. He spent the summer of 2022 following the Batavia Muckdogs, a college summer team in western New York, 45 minutes outside of Buffalo. When the New York-Penn rookie class league was eliminated after 2019, Batavia joined the Perfect Game Collegiate Baseball League, a 16-team summer league of unpaid amateur players and in partnership with Perfect Game, who seem to have a monopoly on American youth baseball leagues, camps, tournaments and showcases now. While Batavia is no longer a city affiliated with any Major League franchises (after 69 seasons spent with more than 7 teams, the longest being the Cleveland Indians for 24 seasons), they are still a baseball town thanks to this team, and Will attempts to capture what makes baseball important to this community, and what makes these communities important to baseball. We talked a little about his life before writing, the book and how that experience affected his baseball fandom.

Going from walk-on Ivy Leaguer to Airborne Ranger

What got you into baseball growing up?

I lived next door to a playground, probably the same story a lot of kids would offer, especially from that generation. Now baseball is more formalized at younger ages with travel ball and everything. But back in those days it was like The Sandlot. We would all just converge at the local playground and play whatever sport happened to be in season. During baseball season, that was it. That coupled with eventually getting to go to my first Major League game. Unfortunately, I grew up in DC; we didn't have a team at the time. The Orioles were the closest team to where I lived. So it meant going to Baltimore, which wasn't super convenient, but still my dad managed to get me out there on occasion. That was the birth of my fandom and it carried on through adulthood.

You played through college. How good were you?

I was alright. I was a walk-on in college and I only played for two years. That was part of the reason I only played for two years. I realized that you not only had to be as good as a recruit, you had to be better than the recruit because in the event that you're similar, the playing time is going to go to the guy that the coach made various promises too. So my college career was not anything to write home about. But up until that point, I guess you could say I had been pretty good.

What school did you go?

I went to Princeton, so it's Division I, Ivy League baseball. Since I've graduated, in the next 20 years, they've actually gone on to become very good. Part of that’s because the financial aid packages changed and so they're able to attract a level of player that they wouldn't have back then.

You had to really want to play… to walk on and then still take Ivy League classes.

I was grateful for the opportunity to go there in in the first place. I still considered myself lucky.

What drove you to keep playing? I mean, you weren't recruited heavily, were you? You probably could have played in smaller schools.

It wasn't really a baseball decision as much as an education decision. And the fact I just loved the campus and other parts besides the baseball.

You graduated and then shortly after enlisted in the military.

I worked for three years. I was in Manhattan on 9/11, which was basically the catalyst to leave that job and then ultimately to join the army.

So you were part of the surge in enlistments around then?

Yes. Obviously, 9/11 was a horrible thing, but to the extent there were outcomes to it that were good, one of them is that the military did receive a real surge in support. I was going to do the Marine Corps, but they said, we have so many people trying to join now and no one's leaving, we can't even process you for a long time, which is why I ended up going in the direction of the Army.

When you were deployed in the Middle East, were you following baseball at all? After growing up on the East Coast, working in Manhattan, Ivy League degree, now you're overseas with people from all kinds of backgrounds. What helped you find common ground with your platoon mates?

I followed it, to the extent we were able to. We did get the Armed Forces Network, which carried some games. We had periodic access to the Internet, so we could stay up to date and see how our teams were doing. That year that I was over there, 2006, I'm a Mets fan, so that was the year the Mets had a very dominant regular season. They had a really strong team. They ultimately lost in a pretty epic LCS to the Cardinals. I was friends with a Cardinals fan and we actually did get up in the middle of the night and try to watch those games. I think 8PM Eastern Time was something like 2 or 3AM Iraq time. That was an amazing series. Unfortunately, the Mets came up just short in Game 7. Watching the games was provided a little bit of happiness in what was otherwise kind of a stressful year.

That NLCS produced one of the greatest catches of all-time by Endy Chavez:

Researching and Writing Homestand

What made you decide on this topic for Homestand? Your previous book was about Iraq and Saddam Hussein, so a little different.

I had always played baseball, from when I was a young child all the way through two years of college. I think that background, coupled with the fact that when I got news of this planned contraction, I had been doing a lot of reporting in small town America. I was somewhat familiar with the role that Minor League Baseball had in some of these communities by virtue of that reporting. I connected these dots, my background in baseball and my understanding of what baseball meant historically in some of these parts of America. And I concluded that this plan to eliminate 40-plus teams just wasn't going to be a good development for these communities. So that was really the genesis of the book.

In the book you describe a small town with a vibrant community where most people are generally polite, pleasant and neighborly. You also mention the abundance of Trump and MAGA signs, flags and apparel, so today’s political tribalism is part of daily life there, as well. What did you take away from that experience that can apply to the country as a whole?

I was mostly interested in getting to know the people as sort of multi-dimensional people. I tried the best I could not to even ask who they're voting for because I didn't want to reduce them to… well this person's an avatar of this party, this person is of that party. I was much more interested in who they actually were.

For example, there's a woman, she loved the author Thomas Hardy. I was much more interested in learning what book she was reading than who she was voting for. I mean I also wasn't dumb; if you spend an entire year with someone, you can probably deduce who they're likely to vote for just by connecting the dots. I was probably aware of that, but I tried not to use that as the filter through which I saw everything. Even to the extent that I probably could conclude with some confidence what their political leanings were, it was nice to see them coming together with people whose leanings I kind of deduced were of the opposite side.

I write about how these two women from Buffalo, who I think I could safely determine were most likely liberal, became really good friends with the security guard who was probably a pretty hardcore MAGA Trump person. Were it not for this ballpark as a place to bring them together through this shared thing that they liked, those people either would not have crossed paths with each other, or they would have, but it would have been in a much less happy, friendly way.

I saw these ballparks a civic asset. A place that that makes our society a little more healthy. Obviously, I wasn't under the illusion that this is going to solve every problem with partisanship that we have in our country, but to the extent you can have places like this, it's better to have them than to not have them.

What do you think needs to change for the business of baseball from a macro level?

If I could just wave a magic wand, I think there needs to be a recognition, and I think there are plenty of people that do understand this even within the baseball world, that these minor league teams serve a larger purpose than just identifying and developing the next Bryce Harper. In addition to just whatever it is you may or may not owe these communities that have supported you for 100 years, there's a lot of benefits to these teams beyond that.

These are the future ambassadors of the sport. Just because a 37th-round draft pick doesn't make the major leagues, it doesn't mean that they're not going to help grow the game in important ways. These are the ones that go back, become high school coaches, Little League coaches, and help sort of inculcate the next generation into this sport. There's the benefit of having a geographically diverse fan base. And there's no better way to get the next generation of kids interested in the game than having them be able to go to a game.

If there's just a handful of Major League cities and then nothing in between, you're leaving a lot of potential fans behind. There's just this ecosystem that contributes to the long-term health of the sport. And it really is not this unduly burden financially. One of these teams costs about $700,000 to support for a season. You're talking about a sport where there are individual players who are making that much in 3 games. So the money is there, it's just a question of how people choose to spend it.

You've been around the country a lot, especially as a writer now. Are there any other places similar in America where people get together and they're able to just have a good time regardless of status?

I mean, I'm not gonna presume that this is the only place and if we lose it, it's hopeless. But I do think it is special. There's not a lot of them in some of these towns that I was in. I think it's important also, some baseball fans from big cities are familiar with what it's like to go to Yankee Stadium or whatever Major League ballpark is in their city. But I don't know if everyone really recognized what it is about these games that are so special unless they've had the chance to go to one. That's also what I try to communicate in the book is just how different it is. Partly just for economic reasons: $99.00 you get a season ticket. $99, you're lucky to get into some of these Major League ballparks for a big game. And because of that, you see the same people throughout the course of the summer, the same friends and neighbors.

I think there's a generational element to it you don't find as much at Major League ballparks. It's easier for an 80-year-old that lives two blocks away to just walk out their front door and two minutes later they're in their seats, it's just not easy for an older person to get to some of these Major League stadiums. You park half a mile away, you have to walk, just to find your way to the seats, it's a long, difficult walk, you're surrounded by 50,000 other people. Whereas here, the ballpark was, and many of these ballparks are, just right in the residential community, they can walk there. And for those reasons, the experience really does resemble more of like a community picnic or a family reunion than a major professional sporting event. There's something unique and special about that atmosphere.

I hadn’t really realized that, yes, it is really hard for elderly fans to take in a Major League game. At Chase Field, you have to walk a block or two minimum from where you parked (and avoid heat stroke). The line to get in is slow-moving, with security checks, metal detectors, and all the apps and Internet access you need to present your ticket. The upper deck is too steep to safely navigate at 80+ years old. The only real option for seating is the lower concourse, and that’s $50 minimum most days. Most things in the stadium are set up to extract money from your bank account. It’s loud, whenever there’s a home run the whole building goes into a flashing light show like a rave (even last week when a 9th inning home run by Tim Tawa cut the deficit to… 10-1). Just look at the chaos after Eugenio Suarez’s 4th home run of the game in mid-May.

Compare that to minor league stadiums, with mellower crowds, more accessible concourses and much more affordable for those who may be on a fixed income, and it makes a ton of sense why MiLB and independent leagues are so important to the entire fan base.

Post-Homestand Baseball Views

You're in Pittsburgh, now? Do you go to Pirates games?

We do. I'm a little conflicted. I have a 7-year-old son now. He's started to develop an interest in baseball. He actually didn't have it as much when I wrote Homestand. It’s funny; in the book, I talked about how he's very much into Pokémon and Star Wars and Legos, and I'm trying to get him interested in baseball. And it didn't really click until the book was finished. All of a sudden he developed this interest, so now he is interested in baseball.

PNC Park, as we all know, is a wonderful ballpark. It's a great place to watch a game. But at the same time, the owner is famously miserly, won't spend any money, and so I'm conflicted because on the one hand, it's a great place to watch a game, but on the other hand, he's charging essentially Major League prices to put out a substandard product for the better part of 20 years. It kind of leaves you, as a fan, in a little bit of a predicament.

Do you think you would still feel that way if this was, say, 10 years ago, before you wrote the book and before some of the minor league business decisions happened?

Yeah, that's a good question. The book definitely opened my eyes up to some of the business parts of the game that were disillusioning. Maybe I'm just more attuned to it. Back 10 years ago, I probably would not have thought about it so much, or not even been aware of it. Probably like a lot of fans, you just go to the game, you hope your team is good, and you don't really see how the sausage is made, so to speak. But once you start connecting those dots, it is almost like a curse, because the more you know, the disillusion in some of these things. I might have had a different attitude back in the old days. I probably would have been just as frustrated that the team wasn't good, but I wouldn't have really dug into why.

You grew up, you played with all your friends and organically built this fandom. Is it different for him? I mean he's only 7, but do you see a difference between yours and his interest in baseball?

It is, I think, very different nowadays simply because we're so saturated in media, whether it's social media or television or whatnot. Back in the old days, I remember there'd be the game of the week on the weekend, and then This Week in Baseball was a really big deal. There was this highlight show for 30 minutes a week, whereas now it's 24/7. There's 100 channels you can choose from that will provide that kind of content in addition to things like YouTube and Instagram. The opportunities to immerse yourself in that part of it are endless. It's very different.

Back in the old days, as many of us remember, you look at the newspaper, you read the account of the game, you look at the box score and that's kind of it. Maybe you're lucky enough to go to a game. Maybe the local team is on TV once in a while. I think, to an extent, that the slowness of it, or maybe the patience that we had back then, is not as common nowadays because you're used to everything in these really fast, bite-sized doses, whereas before, you'd have to spend sort of a lot more time to access those highlights.

So it won't be a slow burn, I guess.

Yeah, it's good. I think for kids, it's great to some extent. Being able to see more baseball is a good thing as long as you still know when to turn the TV off and actually go outside.

What is it about baseball to you that keeps you a fan and loving the game?

It’s a tough one to answer without veering into the realm of overly romanticizing it. That's always the criticism of some baseball books and movies is that it's this idealistic vision that's never really been real. I was certainly aware of that when I was writing the book and you don't want to go overboard. But there is something to that. There's a reason why so many authors and movie makers go that road. There just is something a little bit romantic about it. So for me, and I'm sure for a lot of others, it goes back probably to childhood and just nice memories that you had of games and going there with your parents and with your brother, playing with your brothers and sisters in the backyard or the local playground. So for me, it kind of helps connect me to some of those memories that I've always appreciated and valued. The game, yes, it's changed a lot, but at the same time it's still the same. It’s the same distance between the bases and the same rules. There's a constancy to it that is pretty neat. That would probably be the continued allure of the sport for me.

I love this book so far, I grabbed it at Barnes & Noble on the New Releases shelf (the cover caught my eye…) I’m about halfway through it as of this post, and I am very grateful to Will for taking the time to answer some questions and talk about the book and his experience with baseball. He really captures not only the atmosphere of baseball and the small town, but also makes you feel like you personally know the subjects in his book, from the fans to owners to concession workers. You can grab it at the link in the intro to this post, or you can check out his website here: https://www.willbardenwerper.com/

And with school out and baseball season in full swing, if you have a chance to get to any baseball game in the lower rungs of the sport, from triple-A to college summer leagues, try to take in a game or two. While I personally love going to these games more than MLB, I’m not saying it has to replace the Green Monster and Dodger Dogs and McCovey Cove, just that there’s a feeling you get at these other games that you can’t get at an MLB stadium.

My personal favorite minor league park? Excite Stadium (formerly San Jose Municipal Stadium), home of the San Jose Giants and built back in the 1940s. It’s an old school park in the heart of Silicon Valley where you get to sit on a wooden plank for a few hours and watch a bunch of fresh new faces you probably don’t even know the names of, with a cheap beer after the Beer Batter and fun conversations to be had with fans in whatever section you’re in.