Interview #53: A Civil Steroid Era Discussion

A chat with Dan Good, author of "Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever"

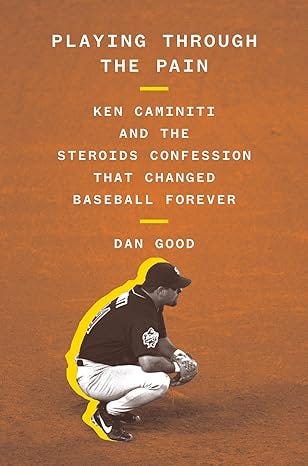

Dan Good is a published author, current ghostwriter and longtime national news journalist. He is also a lifelong baseball fan (especially Juan Gonzalez and the Texas Rangers) who wrote the book Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever. I was looking up Ken Caminiti for something recently, probably an Immaculate Grid reference, and came across this book. Caminiti was one of my favorite players growing up. The MVP third baseman for the ‘96 Padres and part of the 1998 NL Pennant winning team, he was a badass that I, as a fellow third baseman in Little League, tried to copy and did so very poorly.

We talked about his book, journalism and obviously baseball, especially looking back at the height of the Steroid Era in the late 90s. He’s also got his own substack that you can check out. This article is the one I’m referencing at some point in the conversation:

You can get more of Dan here:

Link to the book: Playing Through the Pain: Ken Caminiti and the Steroids Confession That Changed Baseball Forever

Substack:

His website: Good Ghost Writer

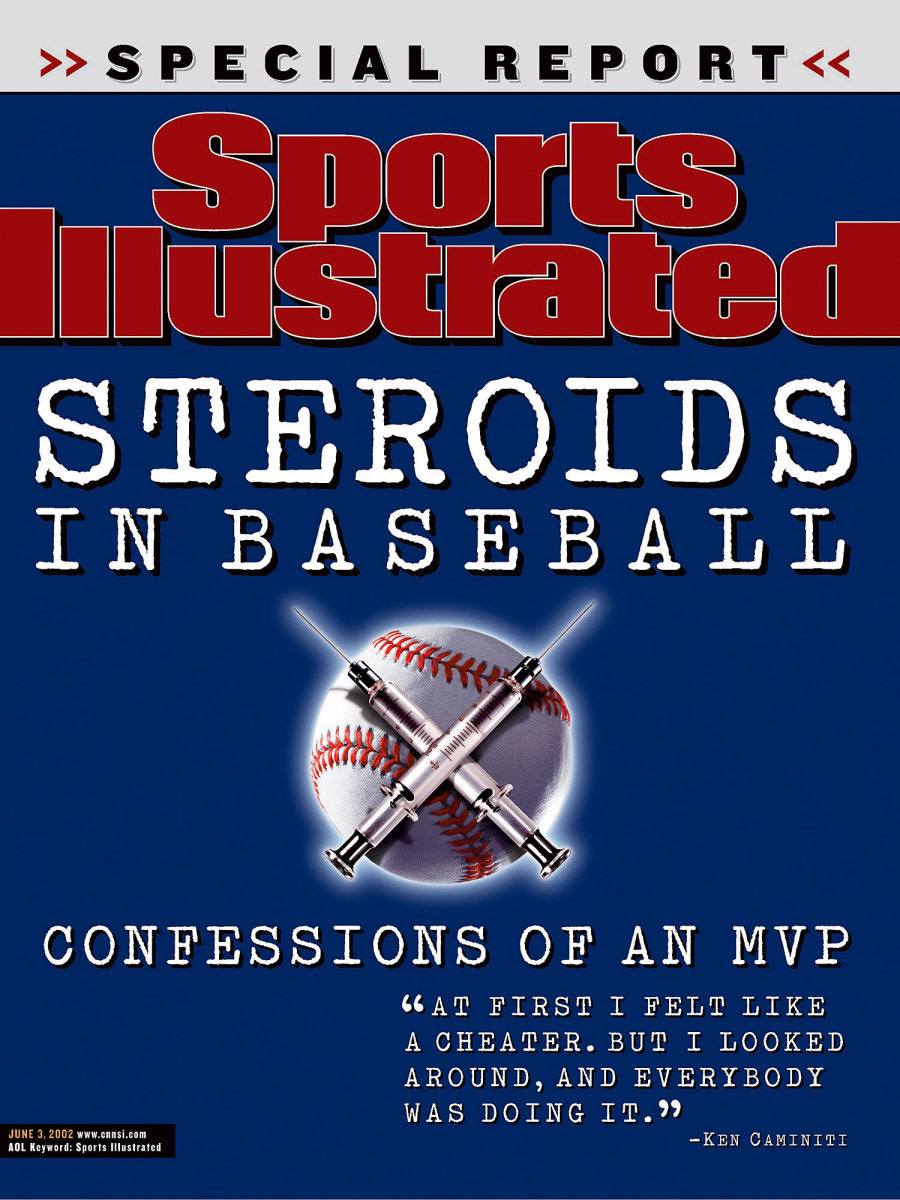

Also, the Sports Illustrated article with Caminiti’s confession in 2002 can be read here: Totally Juiced: Confessions of a former MVP

Baseball Leading into a Journalism Career

Ken Caminiti was one of my favorite players growing up. Somebody put something up recently about him and I was like, I hadn't seen that book yet but I’ve read the Sports Illustrated article. So I started reading up this morning, I read a few of your articles. Is baseball your favorite sport?

It is my favorite sport. It stuck with me. I played football in high school just because, but baseball was always my favorite.

Why did you play football? You said you in one of your articles you were smaller in high school.

I was hoping for a growth spurt that didn't happen. I was like 5’6” up until my junior/senior year, and then I grew to 5’11”, 6’. It would have been nice to have that size. Freshman year, I missed baseball tryouts because I had chicken pox and bronchitis the week of tryouts. I missed my freshman baseball season. I played over the summer, and I batted like .156. I wish things had turned out differently. Not that I would have been that much better, but I think it's interesting because, when you're growing up, it's not like you're thinking I'm gonna practice and practice and practice and work on it outside of practice and get better. If I had the work ethic then that I have now, I think I would have been pretty good and stuck with it, but at the time I'm just like, oh, this just passed me by. I’m just going to move on from it. But it was always my favorite sport. It always will be. How about you?

Yeah, I was kind of born into it. And I didn't resist it, so. Do you think you would have made the team if you hadn't been sick?

I was a good fielding, bad throwing, contact hitter first baseman. I didn't have a lot of power. I could hold my own, but here's the thing I've learned over the years. I remember there were points in time during different seasons where I was slumping. It takes a lot of mental effort to be good at baseball. It's not an easy thing, especially when you're a kid. There was one season in 6th grade where I had different coaches showing me how to do different batting stances. And my whole season was a complete wash. It takes a lot to be able to push through that.

I think I had talent to be good. It's not like I had tons of physical ability; I was an adequate athlete. It's interesting, I think the mentality, the emotional side of it, the struggle, can drive a lot of people away because it's so tough. Any other sport, you're like, ok, I'm getting the ball, I'm gonna take another shot, I'm gonna break out of this. Baseball, there's a lot of waiting around, so the waiting around can be really tough because you're like, when am I gonna hit again? When am I gonna get another chance? And it just compounds to the point where you're like, how am I going to break out of this? So it's interesting when you see Major League players struggle.

So your playing career ended and you wanted to stay involved in baseball?

8th, 9th, 10th grade, I'm realizing my baseball career is gonna be ending. I'm like, how can I stay associated with the game? I think that definitely led to wanting to be a sportswriter, which led to being a news journalist, which led me to want to dive back into a book. I'm like, I know I'm not gonna be a professional. For 99.9% of us, that's never gonna happen. So it's like, what can I do instead? Luckily for me, writing was a talent and something I love.

On the community level, there's so much need for reporting and there's so much opportunity for people to be able to cut their chops and find their way and contribute on the community level. A lot of those jobs don't exist anymore.

You’re one of the few journalism majors in my generation to turn journalism into an actual career.

I remember when I first entered the journalism industry, I graduated from college in 2006, and then the financial downturn happened in 2008, 2009. I came in when the good times were ending, but it was still ok. Classified ads were the financial support of the entire newspaper, and then Craigslist came in and classified ads weren’t a revenue driver anymore. Those years where journalism was generating 25% profits year over year went away and then everything tightened up. Social media came into play, for good and for bad. It was great to be able to news gather, but then it took away from the impact of journalism.

It's this give and take. It's a struggle to see where things have gone and how few jobs there are out there. There's fewer jobs and fewer opportunities. It's a shame because I think, especially on the community level, there's so much need for reporting and there's so much opportunity for people to be able to cut their chops and find their way and contribute on the community level. A lot of those jobs don't exist anymore.

Did you go to college to be a sportswriter, or did you go for general journalism?

To start off, I wanted to be a sports journalist. When I was in 11th grade, I was still trying to figure out what I wanted to do with my career and my life. My grandfather, who was an engineer at GE, he wanted me to get into science, chemistry, all these sorts of things. I came home from school one day and the Sports Illustrated End of Year issue was in the mailbox. I got to the back page, to the Life of Reilly column, and I was really moved by what he wrote. I was like, man, this would be cool to be able to do this for a career, to move people with your words.

And I was like, what's stopping me? That little moment really sparked this journalism focus, and for a while that was sports journalism. I went to Penn State for the early part of my college career and worked for The Collegian, covered golf, women's gymnastics, men's basketball, and really thought that that was going to be the focus. I got the bug for news as well. Then I ended up transferring to Millersville University and really shifted onto news coverage.

What was the last decade like in news? It certainly looks hectic from the outside.

It's been really interesting. Everything started escalating for me when I started working at the New York Daily News in 2015. I had bounced around; New York Post, ABC News. New York Daily News, I stuck around for a little while. It was interesting to see a lot of trends happening, from Trump getting elected and everything that came about from that, to the narrowing and changing and corporate ownership shifts of the news industry. When I was there, the New York Daily News got sold to Tronc for a dollar. It was a real estate deal mostly.

When you're covering the news every day, you're inundated by it. You're just awash with negativity and all these things happening in the world. By that point, my son had been born and I was like, I need to step back, I need to get off this carousel. I remember it was 2018 and that's when I was like, I need to pull back from news, I don't want to do this every day anymore. I still loved it. It was too much. I was facetiming with my son on the train ride home because I missed his entire day, and this happened a lot to the point where I was like I need to pull back.

We found out that there was going to be layoffs at the New York Daily News. I was like, great, I want to get laid off. Let me just get a parachute out and start my new life. We showed up on this Monday and they would call us systematically into these meetings. If you get in this room, you get saved; in this room, you're out. I got pulled into a meeting at the very beginning of the day and I'm like, ok, it's been fun. And they're like, we're laying off your boss, we're laying off all these other people, and you're going to be now part of the change driving the organization forward. There's 15 to 20 people now reporting to me. It was me and another woman running the department.

I stuck with it for another nine months because I wanted to see it through and find some stability. But with everything narrowing, the ability to cover the news has changed. Now you're focused on shorter, quicker hit stuff. Someone tweets something, now we'll cover it. It feels like you're being pulled and led by everybody else. This other person has the story, we gotta match it. Instead of doing your own thing and just being original and creative, which is what readers want. So much has happened with the news industry, now you see corporate ownership bowing down and caving into political headwinds, which is another problem. It's a shame because I think the readers are missing out on really understanding what's happening in the world and in their community. On the local level, you're just not seeing the kind of coverage you used to see.

It’s actually incredible how local journalism feels like it’s vanished. Until Dan brought it up, I hadn’t thought about any local news in ages. Sometimes Scottsdale will pop up on the national radar, like when Paul Bissonette went Jack Reacher on a bunch of idiot drunks in old town. But as for local politics, community issues and things that actually impact us on a day-to-day basis, it’s been relegated to snippets at the end of the news broadcast or whatever outrage pops up on social media.

Which is sad, I remember when we got the actual paper, I’d read the sports page (before my dad could get his hands on it), the Best Buy ads and then the local section. It was interesting to read about community personalities and projects that, for me at least, seemed to increase community pride a little bit. It’s too bad journalism isn’t funded well enough to provide living wages for a full, competent newsroom anymore. Instead the news puts our Orange Leader and his rage bait on and a panel of 15 “experts” to blab about it and provide no actual insight or reporting. Welp.

Ken Caminiti and the Steroid Era

You released the Ken Caminiti book in 2022 after a decade of research and interviews. What prompted you to write it? I remember his confession being the start of the real reckoning with steroids. Jose Canseco came out with his book around that time, too, but no one believed him.

It was a couple things. That was a big part of it. When you go back to the confession, you're exactly right, it's Ken Caminiti and it's Jose Conseco. And you think about their motives. What was Jose Conseco's motive for coming forward? It was to burn bridges. He had an axe to grind and he's just gonna bring the whole thing down. And he's Jose Canseco, he's the ultimate showman. How much do we wanna listen to him? How much is he telling the truth when, in May of 2002, he says 85% of people in baseball are using steroids? You're like, that seems a little high, that's unrealistic.

But when Ken Caminiti comes forward on his own, without really anything to gain other than trying to just clear his conscience and move forward with his life, and he says 50% of guys are using, that was a huge seismic moment. When he passed away in 2004, that really moved me. My dad had passed away when I was pretty young, I was 14. He died in 1997. I was pulled in by these stories of athletes who died young. Walter Payton's another one. Payne Stewart's another one. And Ken definitely did. I was just drawn into his story and the confession. As a baseball fan, I always appreciated and respected him. I felt like there's more to the story. In 2012 I was working overnights at the New York Post, I had all this time during my day and nothing to do. I just started researching Ken Caminiti’s life and that's really what sparked it.

I got pulled in by a lot of things, but ultimately by Ken. I think he was such an interesting person and misunderstood person. You see the headlines of steroid confession and drug overdose death and you're just painting this picture of him. And it was so fascinating talking to people who knew him, who played with him, who were friends with them. He obviously had a lot of problems that he was trying to work through, but he was a really good dude.

Did you have any push back from family members or anyone like, why are you digging into his life now?

There was some resistance. Some people close to him didn't want to talk, didn't want to participate, you know, why are you doing this? And that was tough. I wanted to get everybody on board. I wanted to do something powerful. I was really proud with how it came out, but I definitely would have hoped to have gotten more support from some people close to him. I did get support from a lot of people close to him, but some relatives were reticent to participate.

I get it, because the people closest to him, his family, they didn't ask to be in the public spotlight. A lot of the struggles he faced were self-created. He really worked to fight through them and work on them. It wasn't something that they brought into it. It's not easy trying to help and trying to be a part of that. Think of all the things that Ken went through, addiction, struggle, in the public spotlight, so many people deal with these things in private. He was dealing with them in public. Every time he had an issue, it was in the news. When he gets arrested, he fails a drug test, here's another headline.

It was a tough thing for Ken, and it's especially tough for his relatives where they literally had nothing to do with it and now, just by name, they're getting dragged into it. There was a lot of sensitivity. I was really thankful for being able to talk to the people I did, but I understood it. It was a tough balance, because if I just listened to people who were questioning and challenging it, I would have never gone forward with the book. I just think his story was too powerful to push aside even though they had valid concerns.

So I have my opinion about the steroid era. But what were your initial reactions when it all first came to light? We’re around the same age, so those are the players we grew up with.

My thinking has come in waves. Initially you're not thinking about, oh, this is too good to be true. But when you're looking at the number of players hitting 40, 50, and 60 home runs in any given season, weightlifting and expansion baseball alone aren't going to bridge those gaps. I remember when the andro was found in Mark McGwire's locker in 1998, you kind of brushed it aside. It was not a big deal. I really do think that Ken Caminiti's disclosures in 2002 really opened my eyes to the fact that this was really happening. Obviously, Barry Bonds’ 73 home runs in 2001 raised some question marks.

For a while there was a sense of disappointment internally. My favorite player growing up was Juan Gonzalez. It was Nolan Ryan and Juan Gonzalez. I became a Texas Rangers fan, Juan Gone was my guy. I was nine years old in 1993 when he won the Home Run Derby. That day I had gotten braces, and I had headgear, and I got it tightened it was super tight, like, it was too tight. And I remember that that was the Home Run Derby, he was just smashing balls left and right. Griffey hit the warehouse.

It's disappointing because, you look at all the success these players had, and Gonzalez had two MVP awards, he's one of the iconic power hitters of the 90s. And now his reputation's completely tarnished. I remember in 2001 there was a stop at the airport involving him and they found a package with some supplements and illegal drugs. And you're like, well, that's an issue. At the same time, we don't know. And Major League Baseball completely turned a blind eye.

I went from really feeling a sense of disappointment about some of the players who were known to have used or were suspected to have used, and I've come completely full circle on it. Somebody like Bonds, for example, there's obviously suspicions and frustrations around him. I have a lot of respect for him. I have a lot of respect for the player he was. We've never seen a hitter like that. I don't care what he was putting into his body. We've never seen a hitter that dominant before and we never will again. I don't blame him or anybody else for what they chose to do or not do.

I think ultimately because of the fact that there's so much money on the line, reputations are on the line, and everybody was buying into it. The writers weren't even investigating because they liked access in the clubhouse. So they're not going to start asking questions and writing negative articles about the players potentially using PEDs. They just turned a blind eye to it, and I just think it's very disingenuous now, two decades later, we have the same writers who were complicit to this whole thing turning around and saying, OK, well, this person's not going to be in the Hall of Fame.

I also think that it's interesting when you look at somebody like David Ortiz, who has the statistics and the success, the World Series rings, the leadership to be a Hall of Famer. When you look at his career stats and what he meant, his wins above replacement are less than half of Barry Bonds for his career. David Ortiz failed drug tests. He's in the Hall of Fame, yet we're blaming Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Alex Rodriguez. I don't like Alex Rodriguez. I have a lot of problems about Alex Rodriguez as a Texas Rangers fan. But at the same time it's disappointing when we're holding some accountable and not others.

I think one of the things that really changed my opinion about it was when Bud Selig got named to the Hall of Fame. It's really disappointing to me to think that the person who was most responsible for turning a blind eye to the entire problem is enshrined in Cooperstown, but the players, who were just pawns on a chess board, are being blamed for this. I really blame Bud Selig and the owners and the money than I do the players.

From the perspective of these players, you're great for a long time. Your ability starts to erode little by little. Maybe you're in your 30s, maybe you cap out in your 20s, and you recognize that you're not getting better and you're backsliding. And now what do you do? You're desperate. You are worried for your livelihood, worried for your legacy. I get it. When you think about why people use and why they make that decision, it's not their first choice. There's a reason for it, and a lot of times it's insecurity, fear, doubt. I've really come to sympathize with the players who end up making that decision. What do you think?

I’m not so much mad at the guys who broke the home run records. It's more like, if you're in the minors and you don't wanna use it because it's potentially really bad for your long-term health if you misuse it, and another guy, who's not better than you, gets another 10 feet on his fly balls and ends up climbing up the ranks and he makes millions... I don't think I would have ever tried it if I were in a situation where that’s a decision I need to make because of the health risks.

I go back to when I was playing football. A lot of guys I played with were using creatine at the time and I'm seeing their gains in the weight room, and I'm recognizing I'm nowhere near. I looked at that and I'm like, I don't want this bad enough. I don't care enough to do this. You're right, it's not fair.

It's one thing to say whether or not I get it. The other side of it is, is it fair or not? It's definitely not fair. I definitely feel for the players who decided not to and decided, I'm gonna do it on my own my own ability and see how far I go. It's tough to see those in-betweens, the quad-A player who didn't quite make it. Griffey's upheld as a clean player and like, okay, Griffey's great. Griffey has all the talent in the world. It's easier for him to decide not to have to do that than some guy who's stuck in triple-A and recognizing like, what if I use?

Well, to me, I would like to say I wouldn't risk it for the money. But I didn't grow up poor, so I don't know what it's like to see life-changing wealth as a reward for bending the rules. But also, we let things slide on Wall Street now where people go, oh, that crime didn't hurt anybody, who cares? It does in the long run. But the fact that we let people get away with the little things so much now… I can tell the tide's turning on the Steroid Era and those players are being celebrated again. Except for A-Rod, hopefully he stays out.

But once we got to these insane stats... Barry Bonds was an all-time great player. And then he activated a cheat code, basically. I wonder if any of the less talented players looked at these top players breaking the record books and say, you guys took it too far and killed it for everyone. Ken Caminiti hit 40 home runs and won an MVP while built like a bouncer, but you wonder what guys would have been doing if they didn’t go full throttle with it. But if you’re willing to cheat a little bit, you’re willing to go all the way. And then it just got cartoonish.

That's one of the big reasons I was drawn in by Ken's story. It represents the balance of how far you're willing to go in anything. With somebody like Ken, without any boundaries, without any limits, he was gonna take this as far as he could take it. The interesting thing for me was that Ken was an All Star without steroids; he was an All Star in ’94, wasn't using back then. He was an All-Star player who was derailed from being his best because of drug and alcohol abuse earlier in his career. And ’96, his MVP season, represented clarity. It represented him being the player that he always could have been.

But he had this rotator cuff injury. He started dabbling a little bit in ‘95 and started hitting some more home runs. In ‘96, he really ramped up the steroids. It was in part because of his rotator cuff injury; he injured his rotator cuff the first week of the season and potentially could have missed the entire season. So he really starts ramping up to build up the muscle around his injury and to stay on the field. And that's the cover, that's the thing we tell ourselves. But at the same time, he was always gonna take it as far as he can go. At a certain point earlier on when he was using steroids, he was working with his friend, he was following the right dosages, was doing things the right way.

When things eventually got out of control, as they typically did with his life because he really struggled with boundaries, if this works for a little bit, I'm gonna keep going with it and see how far I can go. It just becomes this self-fulfilling thing. I think he really struggled with it. And then when he started backsliding with his addictions, with the steroids mixed in, it just became this toxic brew. The fact that other players were finding success with it made it easier for him to say yes. And then when he found success through this and became the MVP, then other people are reaching out to him of like, what are you doing? Can you help me out?

I think back then especially, there weren't those boundaries in place. The idea that players would take off for mental health or for addiction, substance abuse and find clarity in their life, I think that's one of the things I struggled with as I was writing the book. There were people around Ken who really tried to help him, who tried to really watch him and monitor him and help him, but at the same time he was still producing. Every time he was struggling, backsliding with his addictions or having problems off the field, there was this balance of, is he still performing? Because if he's performing, he's staying in the lineup. The teams could only do so much to really address the issues he was facing.

I think baseball's better at that now than it was then, but the idea of how far is too far was something that he faced a lot. He was an all-out person, and he was gonna go as far as he could and ultimately did. With top tier athletes, especially, finding that point to say, ok, enough's enough, it's tough for somebody like that.

You have much more insight into the “whys” of the steroid era than 99% of fans and media. What message or thoughts do you want a reader of your book to come away with after finishing it?

I think ultimately we should have an open mind. We should not be ashamed of the players we supported, what they may or may not have accomplished because of PEDs. Again, going back to Juan Gonzalez, I'm still a Juan Gonzalez fan, I will always be a Juan Gonzalez fan. The guy's the man, he was awesome. I tried to interview him in 2006 and he turned me down. He was playing for the Long Island Ducks at the time. I get it. It's not his ideal moment.

Every era in baseball has some level of shame. There's a context or a stigma around every single baseball era. Pre-1947, it was the color barrier and the fact that the players in Major League Baseball weren't necessarily playing against the best players in the world. Expansion era, maybe there's too many teams, or there's too many players who aren't as good. It's easy if you're a 1990s kid to look back in disappointment about the era in which you were raised and say, oh, it doesn't mean as much anymore. I don't think that's the case just because PEDs were in the game back then.

There were PEDs in the game in the 40s and the 50s and the 60s and the 70s and the 80s. There’s still some level of PEDs in the game today. They're always going to be performance enhancing drugs in baseball. Obviously, the drugs got better in the 90s. Let's not kid ourselves there. They were able to do some special things with drugs. Who plays 162 games today? No one does. There's a reason for that. It's greenies. I'm not saying that every single player who was able to play every game in the season was on amphetamines, but a lot of them. There's a reason why players are better at taking a break and not playing every single day.

One of the most interesting interviews I had was with Glenn Wilson. He was an All Star in the mid-1980s with the Phillies and he was talking to me about how he used steroids ahead of his All-Star season (in 1985). It was the only time he used steroids during his career. This was a decade before steroids was anything in baseball and this guy was using it. I don't think that was that surprising. I interviewed Phil Garner, Scrap Iron Garner, the former Astros manager. In the late 80s he had a back injury and he was trying to stay on the field, and he was deciding whether or not he wanted to use steroids to keep playing. This isn't a new thing.

I know there's this sense of disappointment, the things that you upheld and loved back when you were a kid maybe don't hold up the same way now. Maybe the records aren't as ironclad as they used to be, maybe they feel hollow. But I ultimately think you should be proud of growing up in the 90s, proud of 90s baseball, proud of your favorite players. People who read the book should be open-minded about PEDs and the reasons why people could use them, about addiction in general. I think it's ultimately important for us, we have 100,000 overdose deaths in the country every year, to be more sympathetic to people who are really struggling. It's easy to be critical and shame people for the decisions that they make and the struggles that they face. Working on the book gave me a lot of sympathy to Ken and respect to Ken. People who read it should keep an open mind because the things that you think going into it might not be the things you think afterwards.

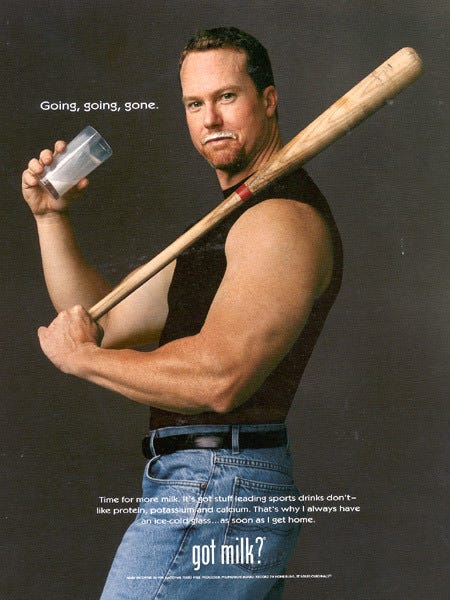

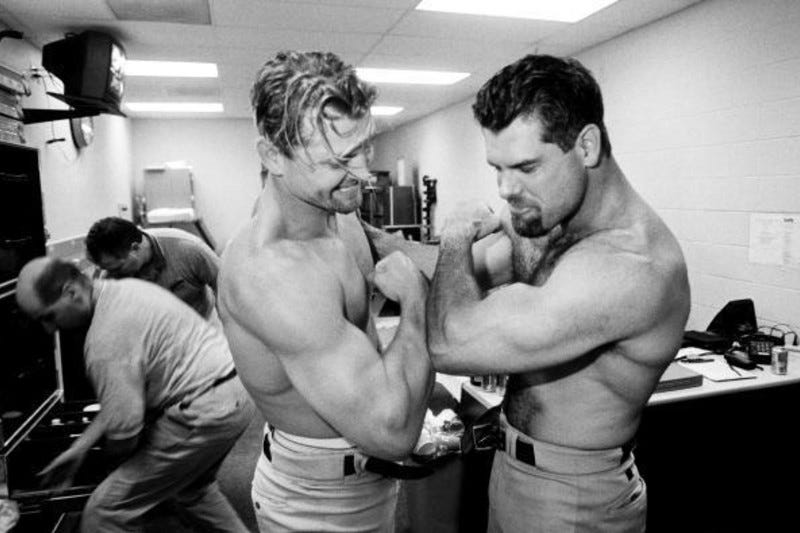

I feel like I’ve had my thoughts on the steroid era pretty cemented for a long time now, but this was the first time in a long time I rethought some of my stances. I still think those who used were wrong, and not getting voted into the Hall of Fame feels like a just outcome (especially the ones getting caught after testing was put into the CBA). But as much as the players failed our expectations of fairness and a clean playing field, the owners and media and fans failed the players by rewarding the cheaters with praise, money and leniency. Plus, chicks dig the long ball:

But it was refreshing to have a conversation about that era with Dan and getting to flesh out the arguments and shine light on a lot of the grey areas regarding PEDs and baseball’s long history of cheating. Most of the time these arguments turn into trench warfare and no one is willing to give an inch if they’re on the forgiveness or punishment side. I’ll see if I can organize my steroid thoughts out a little better sometime soon.

How Could they Trade Jose Trevino?

So what's your relationship with baseball now? Your current fandom. Is your son into baseball at all?

He is super into baseball. He loves the Yankees. I wasn't trying to make that happen. My wife's a Yankees fan and that kind of stuck. I still have been a Rangers fan, so I'm a very happy Texas Rangers fan. For the first 30 years of fandom, it was a rough ride. 2023 that changed, and it was really special to be able to see them winning the World Series. I never thought I'd actually live to see them win the World Series.

My fandom has been rewarded and rejuvenated, it's been a lot of fun. It's fun to see my son getting excited about baseball. He's a huge Jose Trevino fan and he actually met him a little over a year ago and he was sad when he got traded. He got traded to the Reds. He's gonna keep watching him. Nestor Cortes getting traded, he's really into him. He knows more about middle relievers on some of these teams than I do. So it's really exciting to see the game through his eyes and to be able to watch a game with him.

Do you notice any difference between how he's learning the game and how you got into the game, the way you guys absorb baseball? I mean, this is now 30 something years apart.

There's so much more information now. He can automatically watch highlights of the game. When I was growing up, if I wanted to watch a Rangers game, I had to wait for them to be on Sunday Night Baseball. But they weren't on national games all the time, and it was really tough to watch them, and it was really rewarding when they were. But I look at now and it's like, oh I can watch this game right now anywhere in the country, and you can automatically see stats and watch highlights. Baseball Reference didn't exist when we were kids, if it did, I would have spent all my time on it.

Did your dad get you into baseball?

My mom and dad both did. So my dad was a Phillies fan and my mom was a Reds fan. They both got me into it. They started taking us to games, me and my brother when we were kids, either Baltimore Orioles games or Phillies games were both about an hour and a half drive away. They were really supportive. When Joe Carter hit the home run in ’93, my dad was just sitting there stone-faced, he was just devastated. Which I understood now having it happen to me a couple times, like when Altuve hit a walk off home run against the Rangers in the ALCS in ’23.

It was really cool finding Dan and getting to talk at length with him. He’s very good at illustrating his thoughts and you can see why he makes for a good journalist. The determination to track down 400 interviews for a book project as a side project is something a lot of people couldn’t even fathom. I get discouraged when I ask 10 people to interview for this substack and even one of them says no.

If you read this, feel free to leave your own steroid thoughts here. And definitely check out the book, I’m excited to read it in a bit.